The Scenario

Let's say you're wanting to use MiniScript to write a game for Mini Micro. You're making a Shoot'em Up (or SHMUP for short). This is an older genre of video game that used to be quite popular. Let's say you want to make a bunch of enemy fighters for the player to shoot at in rapid succession as they try to shoot back at the player.

Now let's suppose you have a background in an object oriented programming language like Java. For your enemy fighters, you figure you should make a class like this:

EnemyFighter = { "shotStrength":1, "cargo": [] }

We are defining two properties for an enemy fighter:

- The shot strength: how many damage units their shot does to the player ship. By default we want 1 unit of damage.

- The cargo that the enemy fighter is carrying. This will translate to what items will drop when the enemy ship is destroyed. This is how the player will pick up loot.

To simplify the loot system, let's just give cargo a list of integers, with each integer corresponding to an item in some lookup table. Let's spawn three enemies:

enemies = []

for i in range (0, 2) // Remember range is inclusive

e = new EnemyFighter

e.shotStrength = i+1

e.cargo.push i

enemies.push e

end for

We are intending the following:

- The first ship has a shot strength of 1 and a single cargo item of id 0.

- The 2nd enemy fighter has shot strength 2 and a single cargo item of id 1.

- The 3rd and last enemy has a shot strength of 3 and a single cargo item of id 2.

Now adding bullets, collision detection, animations, and the destruction of the enemy fighter are all necessary, but let's bypass that and just test if our code is correct this far. First we'll write a function for EnemyFighter to print its internal variables when destroyed.

EnemyFighter.onDestroy = function(self)

print "Enemy Fighter destroyed: " + self.shotStrength + "; " + self.cargo

end function

Now let's add some debugging to see what happens when the ship is destroyed.

for e in enemies

e.onDestroy

end for

This is what prints:

Enemy Fighter destroyed: 1; [0, 1, 2]

Enemy Fighter destroyed: 2; [0, 1, 2]

Enemy Fighter destroyed: 3; [0, 1, 2]

Oh, that's not good. All three enemy fighters are showing that they are carrying three cargo items!

The Problem

At first glance it might look like we made a mistake and added all of the cargo items to each fighter explicitly in our loop, but we didn't; we added one item per fighter. The actual bug is harder to spot. Can you find it?

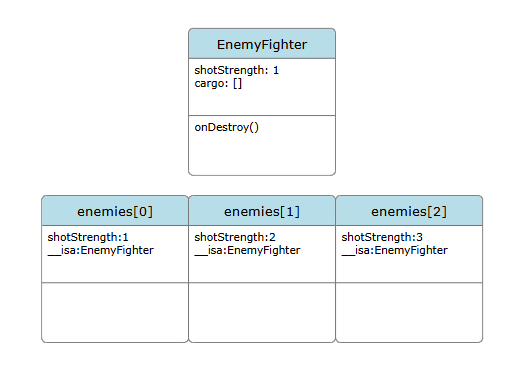

Let's take a peek at a representation of the EnemyFighter class and the enemies list:

There's only one instance of cargo and it belongs to EnemyFighter. In Java terms, cargo is behaving more like a static class variable than an instance variable. Wow. How did that happen?

A Deeper Dive

MiniScript uses Prototype Inheritance for its implementation of Object Oriented Programming. There is no difference between classes and objects. In fact, both classes and objects are just Maps.

When you use the new keyword, you are making a new map with one entry: __isa. This entry is what MiniScript uses to go up the inheritance chain.

But why did MiniScript duplicate shotStrength for every EnemyFighter instance object? Because we explicitly set it in the child instances. MiniScript adds shadow variables to these instances when we set a variable so we don't have this issue.

But why didn't it duplicate cargo for us? Because we didn't explicitly set the value of cargo for each child instance. Instead we merely pushed another element into the already existing cargo list. Where is that existing list? Inside EnemyFighter.

The Fix

There are multiple ways of fixing this. Here's the simple way to fix this example: explicitly add the line e.cargo = [] directly before you push the cargo index value. This will create a separate cargo list for each enemy fighter. The instancing code becomes this:

enemies = []

for i in range (0, 2) // Remember range is inclusive

e = new EnemyFighter

e.shotStrength = i+1

e.cargo = [] // Fixed shared cargo bug

e.cargo.push i

enemies.push e

end for

As an aside, something that might be hard to wrap one's brain around is the fact that the EnemyFighter class could actually be entirely empty of properties, since we aren't using any functionality on this object directly.

Remember EnemyFighter is just a map. It's not inherently an object or a class -- it can be used however we want it to be. The instances of EnemyFighter are also just maps. The problem is simple: if we are editing a list that is actually found in the parent instance, then naturally this will be reflected in all child instances. They are all using the same list, after all.

The Factory Method Pattern

We don't have constructors in MiniScript. Instead, we can make our own factory function that produces objects. Let's rewrite the EnemyFighter class entirely. We want the following features:

-

EnemyFighterinstance creation is handled by a member function that is similar, in Java terms, to a static method on a class. - All instances of

EnemyFighterare stored in a list found within the class itself and shared by all instances. -

EnemyFighter.onDestroyremoves its instance from this internal list.

EnemyFighter = { "Enemies": [] }

EnemyFighter.Create = function(shotStrength=1, cargo=null)

e = new self

e.shotStrength = shotStrength

if not cargo isa list or cargo == null then cargo = []

e.cargo = [] + cargo

self.Enemies.push e

return e

end function

EnemyFighter.onDestroy = function(self)

print "Enemy Fighter destroyed: " + self.shotStrength + "; " + self.cargo

EnemyFighter.Enemies.remove EnemyFighter.Enemies.indexOf(self)

end function

Above is the secret internals of the EnemyFighter implementation. If you are writing a sort of game engine for your team to use, they hopefully don't need to know too much about the above code. Rather, they just need to know how to use it.

Now our enemy creation loop might look like this:

for i in range (0, 2) // Remember range is inclusive

EnemyFighter.Create i+1, [i]

end for

Cleaner! And our debug code to simulate destroying all the enemies could be this:

while EnemyFighter.Enemies.len != 0

EnemyFighter.Enemies[0].onDestroy

end while

This now prints:

Enemy Fighter destroyed: 1; [0]

Enemy Fighter destroyed: 2; [1]

Enemy Fighter destroyed: 3; [2]

Conclusion

MiniScript's implementation of the OOP paradigm can be a bit tricky. This is especially problematic if you experience something like the above while working hard on a 48 hour game jam where time is a commodity you can't afford to lose much of when tracking down bugs. We can mitigate the difficulties by writing clean instancing code, and adhering to certain programming patterns.

I'll leave you with this last thought: It might be argued that MiniScript's implementation of OOP is actually quite simple, but part of what adds complexity is the baggage we are bringing from other OOP languages into MiniScript.

If you agree or disagree, please let me know in the comments. Alternatively, if you have other ideas on object creation, suggestions for better patterns or practices, or related contemplations on MiniScript, also leave a comment.

Top comments (1)

Another great discussion!

One point worth making: the issue you raise (of inadvertently sharing the list among all instances) comes up only with mutable types — lists and maps.

You don't see this problem with strings, numbers, and functions because they are immutable. The only way to "change" the value for these is to reassign it. But lists and maps can be changed without reassignment; they can be mutated in place. And that's where the gotcha occurs, if your intent was not to mutate the shared list/map, but to give each object its own.